SCOUTED: Making the Leap (Part 1)

SCOUTED uses SkillCorner data to analyse the gap between youth and senior men's football

SkillCorner has partnered with Scouted Football, providing data and insights to support their writing on the best emerging talent in football. In this article, the Scouted team used our data to analyse the gap between youth and senior football at the elite level.

One of the most difficult things to get right in football is perfectly integrating players from youth level to senior level, and understanding when they’re ready and when they’re not. The problem? Quantifying the gap in quality between youth competitions and senior games.

The stakes have never been higher. The standard of senior football is the best it’s ever been, with teams drilled within an inch of their lives and dropped points costing, in some cases, millions. The superficial differences between youth and senior football are obvious: youth players are still growing, and their games are more open and higher scoring. But with so much on the line, clubs need a finer understanding of when it’s suitable to port their young stars into the big time. And to reach that understanding, they must properly understand just how big the jump is.

To examine and illustrate that gap, I dug into Under-17, Under-20, and men’s World Cups, and statistical trends from our data partners at SkillCorner. By using key metrics from SkillCorner’s four key categories — Physical Output, Overcoming Pressure, Passing, and Running Off-Ball — I’ll paint the picture of how the game changes as players grow.

In time, we’ll arrive at a clearer understanding of the gap between youth and senior competitions, and offer insight clubs can use to better judge when their star youngsters are ready for the step up.

First, let’s get physical.

Physical outputs

When I had the idea to write this piece, I was immediately keen to look at the physical data. Myself and Llew have really honed in on the physical aspect of development over the last couple of years, and started to get a grip on how much of an impediment it can be to a youth player looking to push into senior level.

Unfortunately, SkillCorner don’t have data on how much players can squat, bench press, or deadlift, but the data they do have can give us some valuable insight into the overall running power between the three World Cups. This can help us gauge the speed at which these games flow.

Needless to say, there are some big discrepancies.

Before getting into all the data, it is worth acknowledging that we are working with minimum three game sample sizes here: it’s not the biggest data pool, but for the purposes of this piece, these World Cups are the three most comparable competitions to work with. So, we’ll crack on.

Let’s start with some basic metrics: PSV-99, and Distance Covered. With all the graphs shown, we’ll start with the men’s World Cup and work our way down to the U-17s.

PSV-99: Peak sprint velocity 99th percentile - This metric reflects the peak speed of a player and its ability to reach it multiple times or sustain it long enough.

HI Running Events: Instances of a player running at a speed above 20 km/h

P60 BIP: Per 60 minutes of ball in play

I will start by saying while some of the changes between these datasets might look small, they are very meaningful.

This is certainly true with the PSV-99 data. The average across the two youth World Cups is a flat 28km/h, while the men’s World Cup averages 29km/h. This is a massive difference.

For context, the fastest players in the Premier League clock in at around 32km/h, with the slowest around 26km/h. Within those parameters, a tournament-wide increase of a full 1km/h is very substantial. A press is executed more quickly, transition attacks become faster, every full-tilt action made snappier.

Consider throughout this piece that every small change has to be multiplied by the 20 players out on the field. Just a five or ten percent difference in an important metric, multiplied across all outfield players, can result in a marked change in the style and quality of football.

I’m sure everyone reading this has heard of the term ‘marginal gains’, and this is, in a roundabout way, an arm of that concept. Just a slight uptick in performance at senior level can make the world of difference compared to the slightly less professionalised — and less athletic — environment of youth football.

Next, here’s another doozy. Let’s take a look at sprinting distance and high speed running distance.

Sprinting Distance: Distance covered above 25 km/h

High Speed Running (HSR) Distance: Distance covered between 20 and 25 km/h

This metric also clearly shows the improvement between the age categories, especially when it comes to sprinting distance.

The U-17s sprinted 136.9m per 60BIP; the U-20s are right around 150m; while the seniors are sprinting 174.4m per 60BIP.

Again, comparing the U-17s to seniors, that is a difference of close to 40m of sprinting per player. Multiply that by 20, and that’s almost 800m of additional sprinting per 60BIP with no fall-off in the high speed running distance.

This, for me, is probably the most enlightening metric out of the the data I have sifted through. It neatly demonstrates the way the pitch feels bigger when you are watching a youth football game. The game becomes stretched more easily because players cannot maintain a professional standard of intensity for the full 90 minutes. Senior games feel more structured and rigid because players are able to take up position in their defensive structure more quickly and more effectively — with the added benefit of better coaching.

Dealing with pressure

Next up, let’s take a look at how all these players handle pressure. Through writing my Gianluca Prestianni and Johan Bakayoko SCOUTED50 profiles, I started to hypothesise that excelling in certain Dealing with Pressure metrics is predicated on both physical and technical qualities, almost in equal measure.

Fundamentally, you can have all the technical quality you want, but if you can’t withstand physical contact then you are going to struggle to maintain possession. Likewise, you can be built like The Rock, but if you can’t control a football… you’re gonna have a bad time.

So, let’s start with the basics. First up, pressures received per 30 minutes of time in possession (30TIP), and forced losses under pressure per 30 TIP.

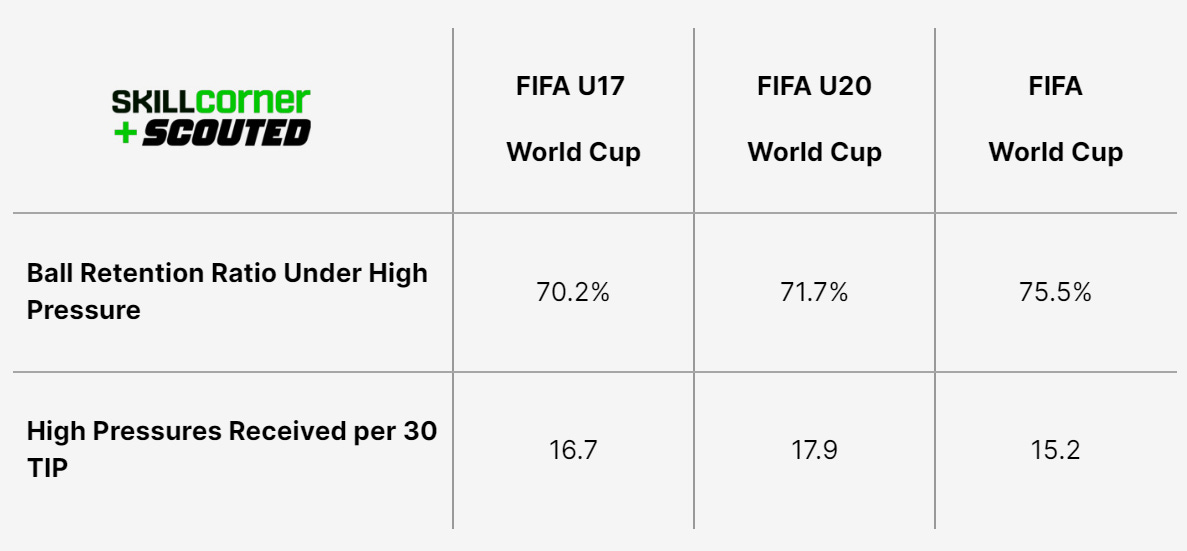

I was a tad surprised to see that total pressures received per 30TIP were pretty level between the U-17 and men’s World Cups, with a little blip in-between at the U-20 World Cup.

Most critically, you’re seeing much less forced losses at the senior tournament — just 6.7 per 30TIP, compared to closer to eight and nine (U-20s are slightly inflated because there are more pressures overall) at the youth World Cups.

We’ll go to the high pressure data and then I will elaborate.

Very interestingly, this time less high pressures are received at the men’s World Cup than the youth World Cups. I did not expect to see this when I pulled the data, but I couldn’t help but be drawn towards the ball retention ratio stats for an explanation.

As you move up the age groups, the ball retention ratio under high pressure increases from 70.2%, to 71.7%, and then to 75.5%.

That got me thinking two things simultaneously. Firstly, that senior footballers are much more technically and physically equipped to deal with the most difficult scenarios to retain possession. Therefore, defenders are more selective in when they press tightly, as they are less willing to break out of the defensive shape with less chance of successfully being able to force a turnover.

Of course, stylistic aspects come into play as well: a lot of the men’s teams in Qatar opted to employ fairly conservative tactics. However, the concept is worth considering more broadly, especially when trying to understand why youth football matches generally see so many more goals and attacking football.

Another interesting explanation for why senior players are better at retaining the ball under pressure is that they are more likely to pass.

Despite our observation that players in the senior World Cup are not receiving more pressures than their youth counterparts, they attempt and complete more passes under pressure. They complete them at a better ratio too, at 82.9% compared to 77.6% for the U-20s, and 77.5% for the U-17s.

Again, this makes sense given our broader understanding of the more conservative nature of the men’s game, but it contextualises how it’s different. Younger players are given more latitude to express themselves, to show their quality, and to make mistakes, while everything in senior football is streamlined for efficiency.

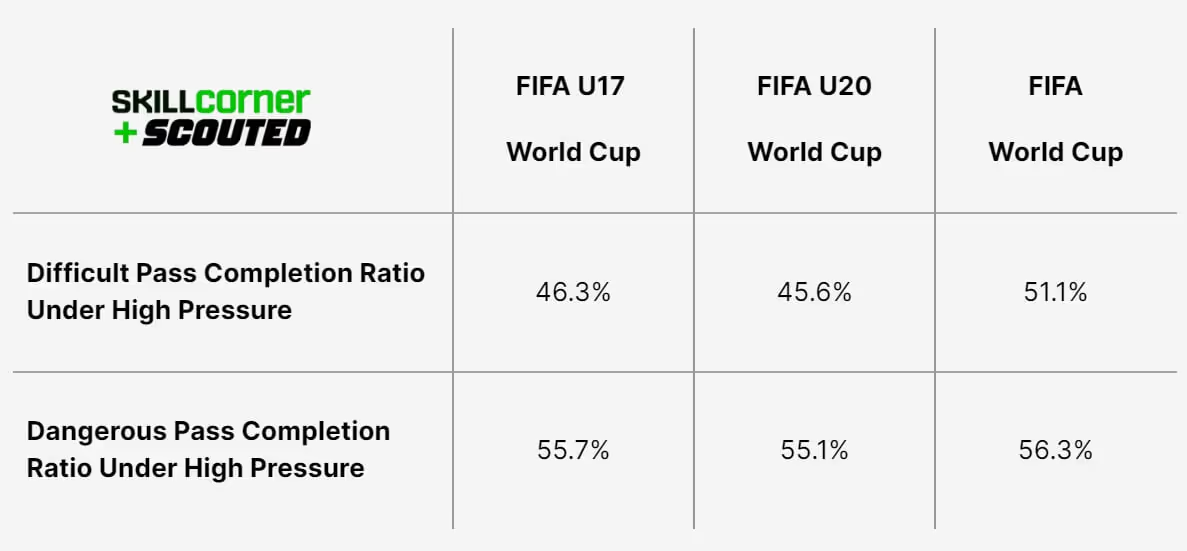

To finish up on pressure, let’s take a look at a couple more execution stats under high pressure.

As you can see, the dangerous pass completion under high pressure is fairly consistent across the three competitions, but there are some very glaring discrepancies for difficult pass completion.

To recap, a difficult pass is: A pass which has a probability of completion below 65%. The probability of completion of the pass is done using the SkillCorner xPass model.

Here, you can see where the senior players again elevate themselves over the juniors. The U-17s and U-20s are executing difficult passes under high pressure 46.3% and 45.6% of the time, while the seniors are up at 51.1%.

I think that five percentage point gap between the U-17s and seniors is very enlightening. These are the most difficult actions to execute, done under the highest amount of pressure, and the highest echelon of talent at senior level is not just edging out their younger counterparts, but clearing them by a massive margin.

Conclusion

So, what have we learned so far?

I think the important thing to grasp is that in senior football, everything is done just that little bit faster.

Senior players need to cover the ground with more intensity in bursts, as they cover a similar amount of distance, but with more sprinting — at higher speeds — than juniors. As I noted earlier, this change, multiplied across 20 outfield players, drastically changes the complexion of the game.

The other important point to extract from this piece is that senior players are able to elevate their game to execute — especially difficult passes — under high pressure much more consistently. This may seem obvious, but it is such a hard thing to quantify with the naked eye — so we can thank the granularity of SkillCorner’s data for helping us further understand what better execution under pressure means and looks like, and how big that gap really is.

Next, we’ll be back to take a closer look at the last two metrics in the SkillCorner suite: Running Off-Ball and Passing, and I’ll come to some broader conclusions about what this all means for how we watch youth football.

Written by Steven Ganavas.

<<Read Making the Leap Part 2>>

Click here for more information on our football products.

Click here for more of Scouted's writing on emerging football talent.